-

Psychotherapeutic Fatigue

Very often my friends and acquaintances, laypeople in the psychotherapy subject, ask me if I bring my patients’ problems home along with me. Somehow, they seem to believe that psychotherapists leave their offices carrying the weight of other peoples’ problems and can hardly sleep at night.

I have always calmly answered that that is not exactly so, as therapists are required to take rigorous professional training, which enables them to distinguish their own contents from those of their patients.

That may be a good answer for laypeople , that will remain so, and also deeply amazed at our absolute skill, although a very unsatisfactory one if we really wish to reach the deep nature of this subject. Even Freud (1910: 1565), who defined the countertransference phenomenon as “an emotional answer from the therapist to his client”[1], was somewhat superficial in this analysis.

More recently, however, due to studies conducted on professional stress and violence and its traumatic sequelae, an increasing number of authors have described a kind of bio-psycho-social disease that affects those who take care of traumatized people. This “disease” is referred to in the literature by various names (Figley, 1995: 9)[2]: “Secondary Post-traumatic Stress Disorder”; “Secondary Victimization”; “Co-victimization”; “Vicarious Traumatization”; “Emotional Contagion”; “Generational Effects of Trauma”; “Savior Syndrome”; “Compassion Fatigue”; “Burnout Therapist Syndrome”, etc.

These authors’ studies do not focus on the patient or on how he may be harmed by the therapist; on the contrary, they focus on how the psychotherapist profession may be unhealthy and have a personal cost to the therapist him/herself.

There are some similarities among the different symptoms of professional stress, mainly when stress is related to excess work and bad working conditions. However, there are specific characteristics of unhealthiness occurring in the helping professions, which is the focus of this article. Being in contact with another’s trauma and trying to help traumatized people causes deep stress to the helper; ironically, the more sensitive and devoted the helper is, the more vulnerable he/she will be to the mirror-effect of another’s pain.

In this sense, I chose the terms – Secondary Post-traumatic Stress Disorder -, as in my opinion it best describes what occurs in the various psychotherapy areas, and Psychotherapist Fatigue.

WHAT IS SECONDARY POST-TRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER?

In 1980, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual – DSM III of the American Psychiatric Association (1989, 264-267)[3] included, for the first time, the diagnosis of Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), to describe symptoms affecting people who go through a psychologically painful experience.

Included in this category are unusual events of human experience that represent serious threats to one’s own life or one’s children and close relatives’ life, such as natural disasters (earthquakes, accidents) or intentional disasters (torture, power abuse).

According to this manual, the trauma may be directly or indirectly experienced through learning about threats and damages to the physical integrity of friends, relatives or close people.

Thus, PTSD – Secondary Post-traumatic Stress Disorder – may be defined as natural behaviors and emotions that arise from knowing about traumatic events experienced by a significant other.

It is a process of gradual emotional exhaustion related to excessive work, and going on vacation only is not the solution; a gradual erosion of the therapist’s spirit, which involves a loss of confidence in his/her own capacity to help. Ayala[4] Pines (1993: 386-402) believes that only professionals with high ideals and motivations experience this syndrome, as if it were a strain between the professional’s need to help and the real problems involved in treating people.

Reviewing the empirical research about this syndrome, Kahill (1988)[5] identifies five categories of symptoms:

- Physical Symptoms (physical exhaustion and fatigue, sleep difficulties, somatic problems like headaches, gastrointestinal disorders, influenza, etc.)

- Emotional Symptoms (irritability, anxiety, depression, guilt, sense of helplessness)

- Behavioral symptoms (aggressive behavior, callousness, pessimism, cynicism, drug abuse)

- Professional symptoms (quitting the job, poor work performance, absenteeism, tardiness, excessive work without breaks, etc.)

- Interpersonal Symptoms (inability to concentrate, avoidance of contact with clients and colleagues, difficulties in personal life, etc.)

Duton and Rubinstein (1995: 85)[6] think that the indicators of this status reproduce in the therapist some of the symptoms of the post-traumatic stress syndrome:

- Stress Emotions including: sadness, mourning, depression, anxiety, fear and horror, rage, hatred, shame.Intrusive images of the client’s traumatic material in nightmares, for example, or in awake fantasies with visual flashes.

- Difficulty in dealing with the client’s dissociation.

- Somatic complaints such as: sleep difficulties, headaches, gastrointestinal problems and palpitation.

- Addictive and compulsive behavior including substance abuse, eating disorders and compulsive working.

- Difficulties at daily social activities and at private life roles, such as: canceling appointments, decreased use of therapy and supervision, chronic tardiness, decreased self-care and self-esteem and a sense of isolation and alienation.

- Physiological excitement.

WHO IS MOST VULNERABLE TO PTSD?

Shortly speaking, all professionals whose fundamental working tool is empathy and all people who are regularly in contact with traumatized people are potentially vulnerable to this contagious traumatization. The so called “helping” professions such as, firemen, policemen and military, emergency and rescue teams, and all professions related to health, such as nursing, medicine, especially psychology and psychiatry.

For many reasons, the last two professional categories are the most affected, from factors related to the choice of the profession to those related to peculiar working conditions.

BEING A THERAPIST: CHOICE OR FATE?

Alice Miller[7] (1997: 30-35) thinks that choosing a helping profession, especially that of psychotherapist, has more to do with fate than with choice itself. She refers to the fact that most therapists come from dysfunctional families where, from childhood, they were demanded to help, directly or indirectly, some less capable adult for that function. Ingeniously trained from childhood to be at someone’s disposal, these people have developed their empathetic ability and sensitiveness which will be their favorite working tool in the future.

Empathy, an essential tool to access the client and to plan a strategy action, makes professionals exchange places with the victims, but doing so they indirectly experience the same events that traumatized their clients. Moreover, the professional’s unresolved trauma will be revived by the report of a similar experience by the client, especially if this experience is a childhood trauma, probably due to the higher vulnerability of the child and to the remembrance of his/her own childhood.

Many authors develop studies on the characteristics of people who choose these professions. High ideals and generous hearts are some traits pointed out by Grosch and Olsen (1994: IX). They have concluded that psychology and psychiatry students constitute a group of optimistic and all-powerful young people willing not only to make money but to change the world; that after hard training along with compassion and care they will be able to transform the life of the people they are taking care of.

Freudenberg, H. (1980)[8] describes the “Type-A” personality, which comprises different traits such as high idealism and performance and low self-esteem; this kind of individuals work harder and harder in order to feel more acceptable. They are excessively devoted professionals who tend to demand too much from themselves and very often substitute social life for work. Some psychoanalysts (Allen, 1979.42,171-175) [9] believe that being successful in their careers will compensate childhood disappointments, like, for instance, unresolved fraternal rivalries or that it will represent a late Oedipal victory.

Victor C. Dias (1987: 187-195)[10] points out to the solitude of psychotherapists, who accustomed to an open and sincere communication, devoid of the usual social dissimulations and hypocrisies, end up by restricting his/her relationships to people who also communicate like him, i.e., to people who have also taken psychological therapy. This trap leads the therapist to be more and more solitary, tending to arrogance, inadequacy and social aggressiveness.

WHAT CAUSES STRESS TO THE PROFESSIONAL?

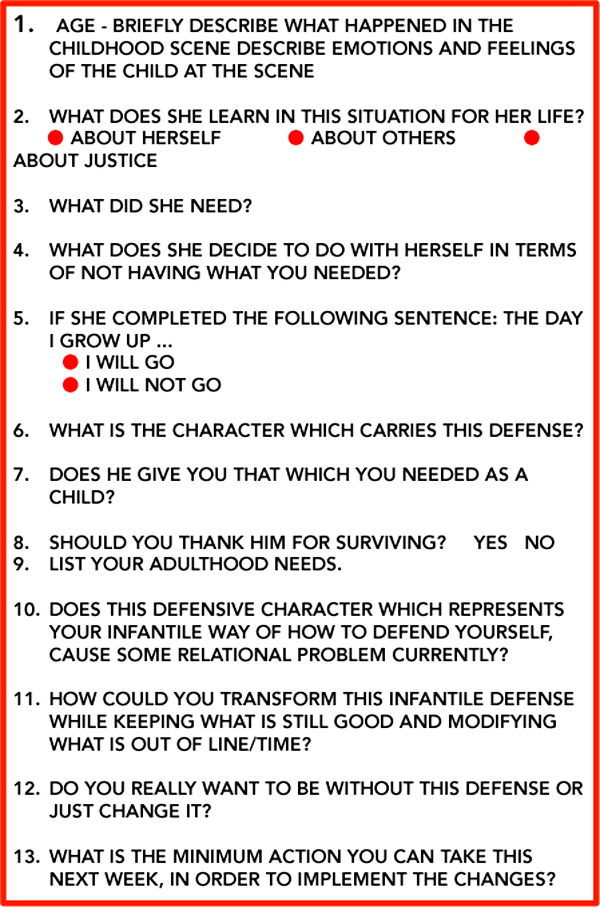

The systemic theory seeks to understand the individual through the impact that involving systems have on his/her life. The circular causality[11]concept may be applied to the therapist’s fatigue issue (see figure 1).

FIGURE 1: MULTI-SYSTEM PRESSURES ON THE PROFESSIONAL

This figure indicates pressures arising from various relationship systems involving the health care professional:

1-PRESENT FAMILY AND PERSONAL LIFE PRESSURE: some authors associate career success with the professional’s middle age, showing that, generally the professional attains his/her top effectiveness between 40 and 50 years of age. Also at this age, life events usually bring dissatisfaction such as: marriage crisis, aging, women’s menopause, children’s marriage, etc. Experiencing these existential crises and, at the same time, taking care of people sorely in need may be exhausting and stressing.

Grosh and Olsen (1994) conveniently describe another frequent situation to us psychotherapists: while we spend hours and hours on end listening to and being empathetic to others, we neglect our own families and ourselves. After long hours listening to patients, how many of us really feel eager to handle our children’s and companions’ routine complaints; how many of us feel like doing physical exercises or having a balanced meal? A study conducted by Michael Mahoney[12], showed that problems like overweight , sleep difficulties , a generalized exhaustion, were some of the most frequent complaints among the interviewed psychotherapists.

Sensitive heroes to our clients, we suddenly transform ourselves in careless participants of our family systems and neglectful of our own bodies.

2- FAMILY OF ORIGIN ISSUES: According to Bowen and his self-differentiation theory, people handle their family of origin difficulties with a large variety of ongoing responses from cutting their families off to completely joining them. There is no self-differentiation in any of these radical solutions. Total fusion or cutoff leaves a work to be done, which will be replied in the individual’s contemporary relationships.

The professional environment is extremely propitious to become a second family, where people play or try to play roles similar to those of their families of origin and where they expect to put an end to the former emotional drama, although they just keep repeating it.

3- CLIENT PRESSURE- In this item, in addition to the constant concern for the evolution and seriousness of the cases of which we take care, I would like to point out another professional fatigue factor.

Berkowitz (1987)[13] describes the “non-reciprocal attention” phenomenon. The author says that psychotherapists seem to be prepared to deal with others’ pain and stress, but they do not seem prepared to the patient’s lack of reciprocity. Constant giving in a one-way relationship with no feedbacks or perceivable success is hard to anyone, especially to someone who has become a therapist to understand his/her own dysfunctional roots.

The therapist’s work implies a constant “affective turn on and turn off” with the other person. Many times, at the top of a therapy process we suppose to be successful, the patient quits therapy or is abruptly withdrawn from therapy by paying parents, with no explanations; this hampers the loss and mourning process demanded by any detachment. Young therapists, mainly, feel deeply upset at these solitary losses, at the sudden divestiture of a relationship they supposed to be strong and productive.

4- WORK PRESSURE, SOCIOMETRIC PROBLEMAS, PRESSURE ARISING FROM WORKING CONDITIONS- The psychotherapy profession has some unrealistic expectations in terms of healing people in a profitable and elegant way. Unfortunately, working conditions, our consultation fees as well as our sociometry are often unsatisfactory.

Our colleagues who perform community services experience various kinds of frustration, from location and attendance to their services to the lack of remuneration. “The institution care client is the one who does not pay, often does not show up and never improves”, says a humorous quotation about the reasons to stress.

Even those who have a private office very often embitter the lack of paying clients, a low remuneration from healthcare insurers, and the self-instability of a self-employed career consequently lacking gratification from the professional life.

PROFESSIONAL ABUSE AND THERAPIST FATIGUE

The therapist’s stress may lead to a careless and abusive service to patients. Some colleagues compensate their low consultation fee by seeing many patients on the same day, or organizing excessive large groups of people, in disadvantage of work quality and of their own personal health.

The therapist’s unrealistic expectations may also affect the client’s development. The urgency to be regarded as useful and to be reassured of his/her professional ability may transform the therapist’s compassion into a pressure on the patient to perform changes in his/her life.

On the other hand, a patient’s worsening may lead the therapist to feel inefficient and frustrated. Taking Kohut’s ideas about the narcissistic issue as a starting point, William Groch and David Olsen (1994: 57)[14] describe some psychotherapists’ arrogance and “God complex”. They believe that psychotherapists who did not experience enough mirroring and empathy in their first childhood years may compensate their desire to be appreciated and esteemed using the patient for this complementary role.

In this sense, the objective of the helping careers is paradoxical: in one aspect they represent a way to transcend oneself; in another they may well serve as a means to gain others’ consideration.

Dealing with people who tend to idealize us leads to two kinds of common mistakes:

- We may assume that they are dead right, that we are really special and so we keep on doing things to maintain their opinion about us;

- We may become so anxious with this load of idealization that we’ll do anything to disappoint them – acting wrong, making stupid mistakes, or being too symmetric towards the patient.

Actually, the therapist’s role implies a certain power, which we must be prepared to assume, without excesses and for a while only. I always remember a supervisor who told me to be absent once in a while and not always replace sessions. Therapists’ faults help to adjust patients’ excessive idealization.

CONCLUSION: PREVENTION AND TREATMENT

There are many ways therapists may use to take care of their own health. All of them invariably imply a change of work and life routine. Determining the number of patients, having reasonable mealtime breaks, doing physical exercises, etc. are some of these ways, which although apparently simple, they are extremely hard to be put in practice.

It is not just a matter of working less, you must substitute a portion of the financial, professional and narcissistic assumption, which comes from a booked up agenda, for the growing awareness that we are as vulnerable as our patients and that there’s no possible way to support others’ needs if we don’t take care of our own needs.

Another desirable way is to balance clients’ attendance activities with didactic activities like giving classes, lectures or institutional work. That makes the therapist mover around, talk to other people; get into more symmetrical relationships than those he/she has with the patient.

Therapy and supervision groups are also very important, as long as they represent a safe place where the professional can expose himself without fearing reproaches and personal critics. In my point of view, a proper supervision group does not exceed 6 or 7 colleagues and implies an intimate work of constructing the professional’s role. Large groups favor idealizations and defenses that end up destroying the information originality.

Organizing small study groups on an issue jointly selected is another kind of group support that reduces professional isolation. These “groups of equals”, in addition to being productive – recycling professionals and producing written work – provide a symmetrical relationship less formal than the supervision. Almost naturally, colleagues share their working difficulties in the clinic and offer emotional control to delicate issues such as: lack of clients, sessions seemingly ill-conducted, “therapist’s love and hatred towards clients”, tips about a service that’s been worrying us, etc. Personally, I am strongly in favor of this resource.

Participating in congresses, experiences and researches on the working area also help the therapist to keep a healthy interest in his/her own personal practice.

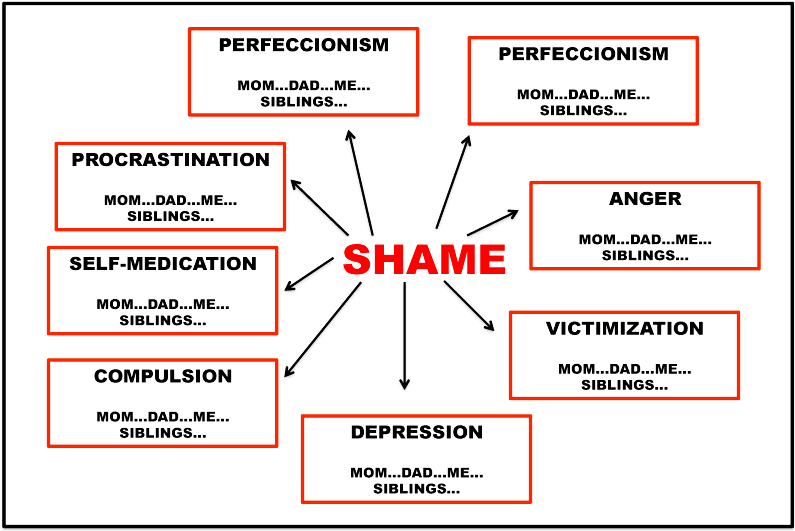

I think it extremely important that we recognize these issues related to our professional performance and would very much appreciate it to have them discussed more often in our congresses. I believe that shame is associated to this matter, as we see each other as semi-gods, and admitting our needs might be taken for some kind of personal fault or failure.

The Greek myth of Asklepius[15], god of healing and father of medicine, gives me support to close this text:

Asklepius, son of god Apollo and mortal Coronis, was wounded before being born; his father Apollo, in a jealousy crisis upon knowing that Coronis had betrayed him, ordered her to be burnt alive. However, when he knew she was pregnant, he pulled the child from Coronis’s womb and gave it to Chiron, the Centaur, to teach him the art of healing.

Chiron, half human and half god, could never be healed from a wound caused by Hercules. Thus, Chiron, the healer, who needed to heal himself, taught Asklepius the art of healing, the ability to find seeds of light and to feel comfortable in the darkness of distress.

The paradox of the helping professions lies in the fact that the healer heals and remains wounded at the same time. All human beings have wounds and despite the excellence of our psychotherapies, they do not exclude us from our own humanity.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC NOTES

- Allen, (1979) Hidden stresses in success. Psychiatry, 42,171-175.

- Berkowitz (1987) Therapist survival: maximizing generativity and minimizing burnout. Psychotherapy in Private practice 5 (1) , 85-89.

- Dias, Victor R.C.S (1987) – Psicodrama- Teoria e Prática- Edtora Ágora -S.Paulo.

- Duton,M.A. and Rubinstein, F.(1985) – Working with People with PTSD: research implications In Figley, R.C. (1995) – Compassion Fatigue, Brunner/Mazsel, Inc, New York, U.S.A.

- Figley, R.C. (1995) – Compassion Fatigue, Brunner/Mazsel, Inc, New York, U.S.A

- Freud ,S. (1910) – El Porvenir de la Terapia Psicoanalitica- in Obras Completas , Biblioteca Nueva, 1973 ,Madrid.

- Freudenberguer, H. (1980)- Burnout: the high cost of high achievement, Doubleday Publisher, New York.

- Grosch, N. W. and Olsen, C. D. (1994) – When Helping Starts to Hurt , W. W .Norton & Company, New York, U.S.A.

- Kahill, S. (1988)- Interventions for Burnout in the helping professions: A review of empirical evidence. Canadian Journal for Counseling Review, 22 (3), 310-342

- Manual de Diagnóstico e Estatística de Distúrbios Mentais (1989) 3ª Edição -Revista DSMIII – R, Editora Manole Ltda .

- Miller, A. (1997)- The Drama of the Gifted Child, Editorial Summus, S.Paulo.

- Pines, Ayala (1993)- Burnout: Handbook of Stress. Free press.. Psychotherapy in Private practice 5 (1) , 85-89 , New York:

- A. (1999)- Aesculapius: A Modern Tale- MSJAMA online: http://www.ama-assn.org/sci-pubs/msjama/articles/vol_281/no_5/jms90003.htm

[1] Freud ,S (1910) – El Porvenir de la Terapia Psicoanalitica”

[2] Figley,R.C.(1995) – Compassion Fatigue

[3] Manual de Diagnóstico e Estatística de Distúrbios Mentais , 3ª Edição -Revista DSMIII -R, Editora Manole Ltda 1989 pp . 264- 267

[4] Pines, Ayala- Burnout-Handbook Of Stress

[5] Kahill, S. (1988)- Interventions for Burnout in the helping professions : A review of empirical evidence. Canadian Journal for Counseling Review, 22 (3)3310-342

[6] Duton,M.A. and Rubinstein, F.- Working with People with PTSD: research implications

[7] Miller, A. (1997)- O Drama da Criança bem dotada

[8] Freudenberguer,H. (1980)- Burnout: the high cost of high achievement

[9] Allen,1979. Hidden stresses in success. Psychiatry ,42,171-175

[10] Dias,Victor, R.C.S. ( 1987) Psicodrama-Teoria ePrática

[11] Circular causality: everyone is related in the system, therefore any change affects all individuals and the system as a whole

[12] Mahoney, Michael – Personal Communication in a workshop on “”The personal life of the psychotherapist”. He is a MD, PhD – from Stanford University, author of various books on the Cognitive and Constructivism approach.

[13] Berkowitz(1987)-Therapist survival: maximizing generativity and minimizing burnout. Psychotherapy in Private practice %(1) , 85-89

[14] Willian Groch e David Olsen (1994)- When Helping starts to hurt

[15] Stanton, J.ª ( 1999) – Aesculapius: A modern Tale

-

FOUNDATIONS OF PSYCHODRAMA: THE IMPORTANCE OF DRAMATIZATION

The other day, one of my colleagues of “GEM” – Moreno’s study group – said something very curious about round tables in congresses. She said that no matter what the table theme is, the debaters always talk about what they like, i.e., they take the opportunity to make public the points of their own interest, not necessarily the ones proposed by the organizers.

I normally follow rules, but when I considered this table theme – Foundations of Psychodrama – it soon came to my mind two ways of approaching it: in the first, I would interpret the word ‘foundation’ as a solid basis that legitimates and authorizes the psychodramatic practice; in the second, I would seek what seems to me to be fundamental, essential and indispensable to Psychodrama.

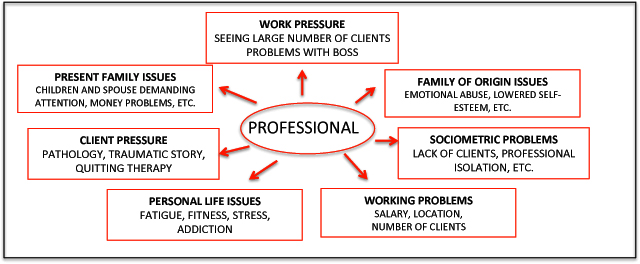

I confess that I was more attracted by the second possibility, as for Moreno (1999:33) Psychodrama is just one of the methods of sociatry, one of the three components of socionomy: sociodynamics, sociometry and sociatry. (figure 1)

FIGURE 1 – SOCIONOMY

Searching for the foundations of Psychodrama would involve establishing the basis for the whole of socionomy, i.e., describing the foundations of all of Moreno’s work. At least, I would have to mention the Morenean vision of the spontaneous man, his philosophy of the moment, as well as his Role Theory and Action Theory. Honestly, I would not be able to do that in 15 minutes.

Therefore, I chose the second possibility, i.e., to understand the word ‘foundation’ as what I consider to be the basic, essential and indispensable attribute to Psychodrama .

Moreno describes Psychodrama in many ways. In one of them he defines Psychodrama as the treatment of an individual or group through dramatic action (1992:183).

Personally, I consider the dramatic action one of the fundamental characteristics of Psychodrama and its absence concerns me, especially in relation to the bipersonal status. Many colleagues, who are teachers-supervisors, say that they do not like and do not dramatize in the absence of an auxiliary-ego or supplied with objects and cushions. I must point out that I do not doubt the efficiency of psychodrama without drama, as I know that the success of a treatment does not lie in one factor only.

What amazes me is that some colleagues do not consider such a fantastic technical tool as dramatization, which therapeutic value has been more and more experimentally proven. Therefore, in the next 15 minutes, I would like to comment on three therapeutic aspects of the dramatic action that seem fundamental to me:

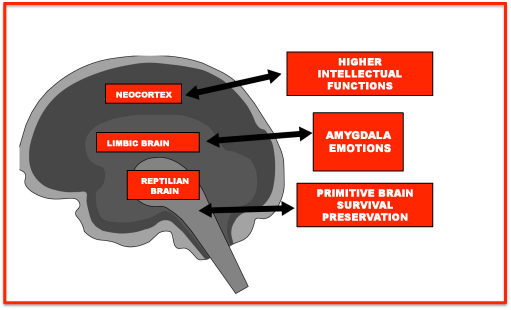

1- IT PROVIDES A MUSCULAR ENERGETIC DISCHARGE, NECESSARY FOR PATIENTS TRAUMATIZED BY VARIOUS CHILD ABUSES OR CARRYING TRAUMA

SEQUELAE OF ACCIDENTS (POST-TRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDERS).

Studies on trauma and its long-lasting effects in people’s lives have proved that Moreno (1959, p.239) was right to say that “act hunger” is a human physiological need just like eating, drinking and breathing.

The immediate response to a stressing situation** releases mechanics of the sympathetic nervous system reaction, known as “alert reaction”. When the animal organism gets ready to fight or escape, its breathing becomes deeper, the blood flows from the stomach and intestines to the heart and to the muscles; the ongoing processes in the alimentary canal cease, sugar is released from the liver’s reserves, the spleen shrinks and releases its contents, the hypothesis stimulates the adrenal glands and the body is flooded with hormones, like adrenaline. That’s an efficient preparation for activity and combat, as Walter Cannon had described, in 1939, and Paul MacLean reaffirmed, in 1952.

Studies developed on the animal kingdom (Levine, 1999) show that when an animal is hindered from reacting, archaic brain mechanics start operating, i.e., the reptilian brain, provoking freezing of the vital functions, thus simulating death. Through this trickery, the animal succeeds to be left by the predator or at least, to gain time to think of another escape strategy.

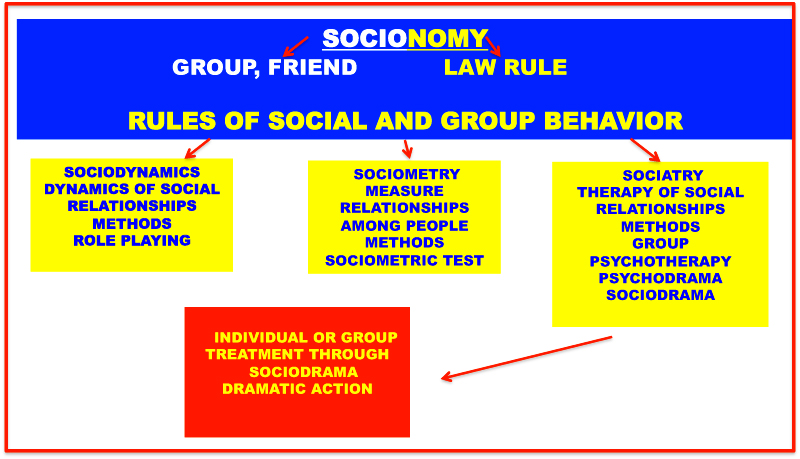

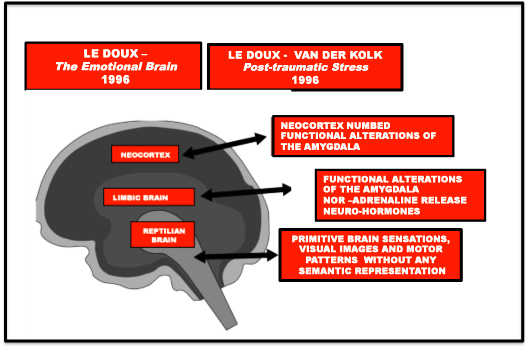

The same occurs, with some differences, to the human animal. In 1952, the American neurologist Paul MacLean described the triune theory of the human brain, a result of our phylogenetic evolution (See figure 2).

FIGURE 2. PAUL MACLEAN “THE VISCERAL BRAIN” (1952)

The brain stem is the primitive, reptilian brain, a remnant of our prehistoric past.

It is useful for quick decisions that do not demand much thinking. The reptilian brain focuses on survival; it is fear-driven and takes over whenever we are in danger and do not have time to think. In a world where the fittest survive, the reptilian brain is concerned with getting food and not with becoming food.

The central part of the brain is the limbic part or mammalian brain, the root of emotions, humor and feelings. The neocortex is the most evolutionary advanced part of the brain. It controls our ability to speak, think and solve problems. The neocortex affects creativity and the ability to learn, comprising approximately 80 per cent of the brain.

As we can see, the human brain is more specific. However, as Le Doux and Van Der Kolk (1996) demonstrated, the brain is not fully functional in traumatic situations, as the neocortex undergoes functional alterations releasing hormones that make it numb. (figure 3).

The memories filed at this moment do not need to be verbalized, they are formed by sensations, visual images and motor patterns, as language is a neocortical function.

FIGURE 3- BRAIN FUNCTIONING IN POST-TRAUMATIC STRESS

Like the animal, the human being when prevented from reacting, functions with the reptilian brain. Freezing of vital functions is shown through superficial breathing and stiff muscles, simulating “rigor mortis” and anesthetized mind, as in an ethereal state. But contrary to the animal, which after the danger is past defrosts through a noticeable body shivering, the human being mingles these physical functions with thoughts, feelings, emotions, invisible loyalties, etc¾ which are results from the other two parts of the brain.

Many times, a person who was raped, for example, conceals his/her horror, refrains from crying, shaking and feeling ashamed to pretend that nothing’s happened. As a result of this non-action, his/her body will not recover from the trauma and the helplessness feelings experienced at the moment he/she was attacked. The individual lacks an offensive action and control recovery, which often are only attained many years later, through the active repetition of violence or abuse, this time taking the role of the abuser or of someone who holds control (many addictions are disastrous attempts to simulate control).

Dramatization allows this missing action to come about, enabling muscles to produce a safe discharge of the body’s need for control recovery. I would like to remind you that psychodrama was one of the first body therapies; Moreno said that the body remembers what the mind forgets, especially events that take place in early childhood, even before language acquisition. The best way to recover the memory of actions is through expressive methods, which address the whole person (body and mind) in the action.

2- IT PROVIDES ACTIVE AND RESPONSIBLE RESEARCH OF THE PATIENT IN RELATION TO HIS PROBLEM

As I described above, hindering of an offensive reaction creates a lethargic and helpless attitude before reality. Needless to say that most of our patients feel like this towards their own lives. They feel that something must be changed, but they don’t feel capable of undertaking this change.

In many talk therapies, especially when interpretation is utilized, the key to the symbolic puzzle, to the meaning of feelings and thoughts, to how they relate to the past, present and future seems to be in the therapist’s hand. The patient is just the patient ¾ he/she expects the therapist to do his job. This only reinforces his/her already known fragility and helplessness.

Bustos has a small picture in his office that says: “what they say about me that was not disclosed by me does not fit me”; Milton Erickson (1983, pp. 45), the innovative American psychotherapist, father of modern hypnotherapy and whose methods inspired the systemic, strategic, familiar therapies, etc ¾ also thought that the direct interpretation of the therapist represents raping to the unconscious of the patient, who releases a host of defenses to dissociate, deny, i.e., to defend himself as much as he can. We penetrate indirectly into the patient’s unconscious, through the back door, with much warming-up, and never ahead of the patient himself.

Moreover, all patients have a sound and combative portion and I particularly make my patients aware of this from day one. I always ask them what they feel like working with in that specific session and I have them play the situations they choose to work. They are active researchers like me. Decoding their material, their emotions, decisions, etc, is our joint task, often their task more than mine.

3- IT OFFERS THE SURPRISE ELEMENT TO A PATIENT ACCUSTOMED TO FUNCTIONING WITH DEFENSIVE MECHANISMS ONLY.

Dramatization has no predetermined script. I never know what is going to happen, much less does my client. I am often amazed at what comes up and I love to see my patients’ surprised look. I surprise them too, playing roles and counter-roles unexpectedly, seeking an interpolation of resistances very useful to stimulate spontaneous-creative answers, i.e., new answers to old situations.

Moreno (1923, p. 54) already mentioned the surprise function in the activation of spontaneous-creative processes. In turn, Milton Erickson (1983, p. 50) used the confusion technique to induce to hypnosis. For example, he would ask a person to imagine him/herself climbing into an airplane flying to the USA and at the end of the trip, after various commands, he would ask the person to find him/herself landing in India. He knew that the surprise tactic unbalances the intrapsychic defenses, compelling the mind to produce a different responsive energy.

The surprise element is also present in childhood traumatic situations or even in accidental traumatic situations, compelling the patient to create a defense that will give him back a feeling of control. Healing provided by dramatization is somehow driven by the homeopathic principle of prescribing the same factor that caused the disease, with the objective to heal it.

I can’t think of anything more anti-morenean than a therapist listening and interpreting his/her patient verbally. It would at least require triggering an internal action in the patient according to internal psychodrama or Fonseca’s relation therapy, doing reverse roles sat down or symbolically favoring his/her amazement and surprise, although without the benefit of muscular associations provided by body movements.

Finally, I would like to say that I believe the lack of dramatization in many psychodrama sessions is due to the unawareness of how and why to dramatize rather than to the difficulty of doing it without auxiliary egos or a group.

Supervising my students, I came to the following list of more frequent questions regarding dramatization:

- How to handle issues related to therapeutic relationship: contract (timetable, location, fee, repositions); patients who do not wish to undergo dramatization, etc.

- What is the objective of dramatization? Is the objective exploratory (like a social atom), experimental (training of roles), or does it aim to repair narcissistic damages? (dramatization of childhood scenes)

- How to choose a scene to be dramatized? How to choose a scene when the patient is too talkative? Who should choose the scene: the therapist or the patient?

- How to establish time in dramatization, i.e., present, past and future? How to go from the present complaint of the patient to the past (regressive scene), or to the future (feared and desired scenes) and then come back to the here and now in the relationship with the therapist?

- How to warm up the patient and keep this warming up throughout the dramatization?

- How to decide which technique to use, among the classical ones?

- Which is best: an open scene psychodrama or an internal psychodrama?

- How not to get lost in the middle of a dramatization session?

- What to do when session’s time is over in the middle of a dramatization session?

- How to finish a dramatization?

As you may conclude, my colleague, the one who says that no matter what the table theme is the debater always talks about what he likes, was right.

I really believe dramatization to be one of the most important tools for psychodrama and I think that better prepared students regarding these topics have less fear to use dramatization and may realize the advantages of using action techniques to help their patients.

Thank you very much.

Rosa Cukier

BIBLIOGRAPHIC NOTES

- Cukier, Rosa (1992) – Bipersonal Psychodrama, its technique, its patient and its therapist, Editora Àgora, S.Paulo.

- Cannon Walter (1939) – The Wisdom of the Body, Nova York, Norton, Quoted by Anne Ancelin Schutzenberger – “Querer Sarar”, Editora Vozes, Rio de Janeiro, 1995.

- Lê Doux, Joseph.(1996) –The Emotional Brain, Editora Objetiva, Rio de Janeiro

- Levine P.A. (1999) – Waking the Tiger – Healing Trauma – Editora Summus, S. Paulo.

- Moreno, J. L (1923). – The Theater of Spontaneity. São Paulo: Summus Editorial, Ltda, 1973

- Moreno, J. L. (1959) – Group Psychotherapy and Psychodrama, Editora-Livro Pleno Ltda., Campinas,1999.

- Van der Kolk, B. Mc. Farlane A. Weisaeth L. (eds.). Traumatic Stress: the effects of overwhelming experience on mind body and society. New York, Guilford Press. 1996

- Zeig, K. J. (1983)- Didactic Seminars on Psychoanalysis by Milton H. Erickson, Editora Imago, Rio de Janeiro

- ** Stressing situation means any situation leading the individual to a state of despair, either for striving to preserve his/her life or the life of a significant other.

-

CODEPENDENCE– do you know anyone who suffers from this disorder?

Someone once jokingly said that the difference between human beings and animals is not so much to do with being rational, but rather to do with the fact that humans have relatives. Perhaps due to the fact of being born “semi-prepared” and having a long childhood in the care of someone who has helped them survive, human beings are animals who engage longer and more in-depth with their predecessors and successors.

Father, mother, brothers and sisters, grandparents, parents-in-law, uncles, aunties and cousins…….. this makes us completely unique and is also the source of our biggest problems!

This is the case of codependence, a type of emotional and bonding pathology, described by human behaviour experts in the USA. The first studies date back to 1983, and despite not yet being classified in the DSM-IV, various books1 have been written on this topic including one already translated into Portuguese.

At first, the description of this disorder included only families of alcoholic patients, but over time its meaning has been understood in a broader context and currently the term “codependence” also refers to the conduct of families and relatives of people who have some kind of serious, chronic, physical or emotional problem.

“A codependent person is someone who lets the behavior of another person control his/hers and who is, in turn obsessed with controlling the behavior of the other person.”

Everything begins with the fact of finding ourselves connected (because of love, obligation or duty) to someone who is very complicated, physically or emotionally ill, and owing to this illness self destroys or no longer wants to live, and apparently needs our support and constant care.

This person could be a child who was born handicap , an adult suffering from depression, a wife or lover who has anorexia, a brother who did not do well in life, a sister who is always getting into trouble and seems to be too fragile to solve her own problems or an alcoholic father. To sum up, the important thing is not who this person is or what illness they have.

The core of the issue is in ourselves, in how we let this person affect our behavior and the ways we try to influence their behavior or “help them”.

I am talking about a reaction to someone else´s self destruction who ends up destroying us. We become victims of other people´s illnesses and the more we try to make this person give up their addiction or change their attitude to life, the less they get better and the more devastated we become.

It seems like our life revolves around them. We do not act on our own accord, but rather we react to how the patient is: if they are well, we are well, we make plans, we are hopeful; when they turn to drinking or get depressed, we put off going to the cinema, doing things and we feel terrible.

I know that many of you already know what I am talking about because you have probably experienced this or attend people who have experienced similar situations. Perhaps what you are not aware of is that some scientists consider this behaviour of chronic help to the other in itself an emotional, serious and progressive disorder. They even say that the codependent wants and looks for complicated people to connect with and can only be happy this way.

I do not think exactly the same way, as many codependents that I have attended were people who were tired of suffering and who really wanted to change, but whether due to upbringing, religion, guilt…. every case is a case -, they were not able to disconnect.

Some common characteristics codependents have called my attention: they are usually people who have a generous nature, they come from emotionally disturbed families and ever since their childhood have wanted to fix things that were wrong; they tend to make themselves responsible and guilty for everything; they very much depend on love, praising, and other people´s evaluations; they think they know best and can deal with certain situations better than others; they lie to themselves saying that “things will get better tomorrow”; “this is the last time” …; they doubt whether they will be happy in the future or if one day they will find true love; they find it difficult to get close to people, have fun and be spontaneous; they alternate over-affectionate care for a person who is ill with aggressive and rude ways of dealing with them; as time passes they feel ever increasingly unhappy, depressed, isolated and violent; they have eating disorders (either eating too much or too little); they end up having some kind of addiction: cigarettes, alcohol, tranquilizers, etc.

Generically, this illness is associated to various forms of child sexual abuse and codependents basically have difficulties in five areas: 1 – low self esteem; 2 – difficulty in setting boundaries; 3 – difficulty in recognizing and assuming their own reality; 4 – difficulty in taking care of their needs as an adult; 5 – difficulty in expressing their emotions moderately.

Is there any cure for codependence? There is no simple answer to this question. In the USA, self-help groups have been set up, such as alcoholics anonymous groups for families, where they try to discuss and offer support to codependents.

My own experience has shown that psychotherapy, especially psychodrama which is an approach that favors the study of bonding, is often very useful in cases where the codependent is disillusioned by their own potential to change the other person´s life and begins to really want to change their own life. The treatment helps and encourages the patient to undertake the necessary changes, to face their abusive past and to change their attitude concerning their ill relative so that they can live more healthily again, even if the relative still wants to die.

Bibliography

- Beattie,Mellody ( 1994) – Codependência nunca mais! – Editora Best Sellers, São Paulo.

- Rosa Cukier (1998)- Emotional Survival: from the child wound to the adult drama, 2007, Lulu publisher.

- Cermak,T.L (1986) .- Diagnostic criteria for Codependency- Journal Of Psychoactive Drugs. 18(1):15-20 citado por Mellody , Pia.- Facing Codependence, Harper & Row, Publishers, San Francisco ,1989.

- Mellody , Pia ( 1989)- Facing Codependence, Harper & Row, Publishers, San Francisco .

-

I HATE YOU . . . PLEASE DON’T LEAVE ME!:THE BORDERLINE CLIENT AND PSYCHODRAMA

Perhaps some therapists have already had the experience of working with a client who becomes furious during the session, complaining about your ability as a professional, about something that was said or even the way it was done. In general, we therapists become very unsure of ourselves at these moments. We do not know how to act, on the one hand trying to find out what we did incorrectly and on the other being absolutely sure that it was more the client’s performance, which then causes us to be angry and sometimes afraid of him.

As therapists, we know it is not easy to admit that we may feel anger and fear toward our clients. However, in the specific case of the borderline client, these are the exact feelings that he commonly produces in the people who are the most intimate and dear to him. Therefore, it is essential that the therapist know this and decodify his own emotions without blame or shame, so as not to act in a complementary way and to be able to help the client understand the psychodynamic involved in the process.

Lineham (1993:3) estimates that 11% of the non-committed psychiatric clients, and 19% of the committed ones in the United States are borderline clients. Among those who are diagnosed with “personality disorders”, 33% of non-committed clients and 63% of committed ones are considered to be borderlines. This type of client is, therefore, frequent enough for one to believe that all therapists, in general, have had at least one case. Besides this, they are also the ones who most commit suicide. It is estimated that 70 to 75% of borderline clients have at least one self-destructive episode or act, with approximately 9% of the cases being fatal (Lineham, 1993:3).

In Brazil, we do not know of any work concerning the prevalence of this pathology within mental diseases. However, considering our own clinics and the experiences of co-workers, we think that something similar must be taking place. What is intriguing is that besides the great danger of this condition, the available therapies fail without exception, and therapeutic advances are extremely insignificant and slow. The clients normally come to the clinics with a list of therapists whom they have already consulted, over medicated (as doctors try several psychiatric medicines to control the symptoms), and their families seem devastated and with no hope of attaining proper help.

BORDERLINE PERSONALITY CONCEPT 3

The term “borderline” was used for the first time by Adolf Stern in 1938 to describe a group of clients who appeared not to be benefiting from classical psychoanalysis, and who did not fit in the “neurotic” or “psychotic” categories. In reality, according to his classification they had a type of borderline neurosis.

In 1980, the condition was included in the Diagnosis and Statistics Manual – DSM III of the American Psychiatric Association4 which initially listed eight criteria (in the following revision, nine), five of which must be present to make the diagnosis of borderline disturbance:

1-Pattern of unstable and intense interpersonal relationships, characterized by alternating between idealization and devaluation extremes.

The borderline client thinks in a dichotomous and radical way. His world, like the child’s, is full of heroes and villains, and not infrequently any slip-up or failure by the hero inevitably condemns him. He does not understand gray areas, inconsistencies or ambiguities. Good and evil do not mix: somebody is either totally good or totally evil. He idealizes and is disappointed all the time, appearing to be eternally searching for the perfect caregiver, the one who will always be correct.

2-Impulsiveness in at least two areas5 potentially harmful to himself. (waste of money, sex, drug use, shoplifting, reckless driving, episodes of voracity).

The borderline lacks the ability to postpone gratification: his behavior results from intense momentary feelings and does not seem to learn from experience. He has an altered notion of time: “yesterday” and “tomorrow” are meaningless; only “today” seems to exist.

3-Instability in showing affection due to accentuated mood reactiveness. (episodes of intense dysphoria, irritability, or anxiety usually lasting a few hours but rarely more than a few days).

The borderline client’s mood can vary greatly in only one day or even in a few hours. He is not usually calm and controlled but frequently hyperactive, pessimistic, and depressed. His reactions are generally very intense and inappropriate for the situation that produced them.

4-Intense and inappropriate anger or difficulty in controlling it. (Frequently demonstrates irritation, constant anger, and reoccurring physical fights).

His fits of rage are unpredictable and disproportionate to the frustrations that produced them. Domestic scenes of the type: screaming, breaking objects, threatening with knives, and hitting/scratching people are typical of these clients. The anger appears after any trivial offense, but in reality seems to come from some underground arsenal, from the fear of being abandoned or disappointed.

The borderline’s anger is directed at those closest: relatives, therapists or doctors. It aims to test the bonds and commitments in an incessant search to find out how far he can push people. It seems to be an incompetent cry for help, as it ends up pushing away the people whom he needs most. For this reason, many therapists stop the treatment early or limit the number of borderline clients whom they treat.

5-Threats, gestures, or recurring suicidal and self-mutilating behavior.

This self-destructive behavior has a double meaning: firstly, it is witness to the depression and despair underlying these conditions: to feel physical pain is, in extreme cases, the only way of feeling alive and/or a very efficient way of distracting oneself from greater suffering; secondly, the para-suicidal6 behavior shows these client’s need to manipulate the people who take care of them in order to get more attention or love. In general, they do not want to die but only to communicate their suffering in a convincing way.Paradoxically, because of being insistent and repetitive they end up driving people away, which makes them needier, more desperate, and with a greater desire to hurt themselves.

Many clients report feeling calm and relieved after such “accidents”, and some scientists try to explain this phenomenon attributing it to the release of endorphins, which are a kind of self-treatment by the organism when in pain. Effectively, both self-destructive behavior as well as the well being it leads to are not easily understood phenomena.

In relation to psychotherapy, this symptom is what causes therapists their greatest problems: they pay a great amount of attention to these behaviors, running the risk of reinforcing them; on the other hand if they are ignored, the client can insist and go on in a progression of attempts to cause a stronger impact, which can result in suicide.

Self-mutilation, except when associated with psychosis, is a type of borderline disturbance trademark. There are many different ways for a person to self inflict harm: he can cut himself, smoke or eat in excess, obviously neglect his body, drive recklessly, etc.

6- Identity disturbance; accentuated instability and resistance to self-image or the feeling of self.

The borderline person lacks a clear perception of the limits between himself and the other. In general, he needs to impress people to keep them around him, and his sense of identity and self-esteem are associated with getting this attention or not. Therefore, he has to always be proving this, but deep down he has a feeling of non-authenticity, of falseness. Even when he achieves success, the borderline gets upset, believing that he did not deserve it or that at any time they will find out he is a fraud and will be humiliated.

That is why these people go from job to job, not sticking to any of them: they always have the hope that the next one will be different and they will feel better there. Literally, they cannot “find themselves”. Many times questions of sexual identity are also included in this confusion, since in the same way that the borderline does not know whom he is, he is also not able to decide what he desires.

7-Chronic feeling of emptiness or boredom.

The absence of a strong sense of identity must culminate in a feeling of existential emptiness. This is so painful that the borderline searches out impulsive and self-destructive behaviors to get rid of this sensation.

8-Frenetic efforts to avoid real or imaginary abandonment.

In the same way that a child is not able to distinguish between the occasional absence of his mother or her death or disappearance, the borderline experiences occasional loneliness as a sensation of complete and eternal isolation.

He cannot tolerate loneliness, becoming gravely depressed with real or imaginary abandonment as he loses the sensation of being alive. His existential motto appears to be: “if others interact with me, than I exist.”

9-Transitory paranoid ideation related to stressful situations or severe dissociative symptoms.

In high stress situations, the borderline can show temporary dissociations, confused and delirious thinking, and paranoid interpretation of the facts. In general, he presents himself as a victim of an unjust situation.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The differential diagnosis between the various personality disturbances is not an easy task, as mixed conditions with similar symptomatology are common. In reality, the borderline disturbance is compatible with various other pathologies, making it difficult to know what came before – for example, if the personality disturbance came before a period of depression or alcoholism or if it were secondary to these occurrences.

Many times the borderline client presents a paranoid and split ideation, only differentiating himself from paranoid schizophrenic clients because the crises are faster and do not cause acute after effects like in schizophrenia. Besides this, the schizophrenic ends up getting used to his deliriums and persecutions, being less disturbed by them than the borderline.

In relation to diseases of intimacy, mainly bipolar ones, there are similarities relative to sudden changes of mood. However, in the borderline these changes are faster and, even in the period between crisis, he has difficulty in adapting to reality. It is also possible to confuse a borderline with a chronic hypochondriac, as they both maintain intense physical complaints to achieve bonds of dependence with family members and/or doctors.

Many authors still believe that there is a high prevalence of borderline disturbance between clients who are diagnosed with multiple personalities or post-traumatic stress.

Herman (1992:123-129) studies survivors from various types of trauma (such as varied forms of child abuse, rape, war, etc.) suggesting the generic name of “Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Syndrome” to include all these conditions. She correctly argues that the “borderline personality” diagnosis has caused more damage than benefit for the study of personality disturbances. Like the term “hysterical” whose negative and pejorative connotation ended up becoming psychiatric jargon, the word “borderline” has come to mean manipulator and troublemaker over the last few years. This makes it impossible for the clients to be viewed as heroic survivors of severe childhood drama, with all the respect that this fact requires. This author also shows that the psyche has and uses some defensive resources against limiting- situations that make an attempt against human dignity. Dissociation, intrusion, irritability, self-hypnosis, impulsiveness, intense mood swings, self-mutilation, etc. are some of the defensive tools that will later constitute the different conditions of personality disorders.

Another dysfunction that is often associated with the borderline personality is the narcissistic personality disturbance. It is especially noteworthy because of the presence of a hypersensitivity to criticism and that any failure can cause grave depression. The great difference here is that in the long term the narcissist ends up being, in general, professionally successful. He works very hard to construct and keep up his powerful public image, being deeply self-centered and not getting personally involved with others. The borderline, on the other hand, does not have staying power or discipline and destroys bonds of affection and professionalism. Besides this he is sleazy, insistent, and very vulnerable to others’ opinions.

As far as the diagnostic similarity to clients categorized as para-suicidal in the AXIS and DSM diagnostic manuals, there are in fact symptoms common to both conditions such as: accentuated emotional loss of control, irritability and hostility, serious interpersonal problems, patterns of behavioral loss of control, drug abuse, sexual promiscuity, and previous suicide attempts. The cognitive difficulties are also similar: stressed cognitive rigidity, dichotomous thought, little capacity for abstraction and problem resolution. Such cognitive difficulties are related to the episodic memory deficit. The individuals affirm that their behavior is to escape an unbearable life.

It seems certain that the behavior that most differentiates the borderline from other conditions of personality disturbance is the presence of self-destructive acts and suicide attempts. Among those who show the eight DSM-III-R criteria, 36% kill themselves, compared to 7% of those who show five to seven of these criteria.

ETIOLOGY

Three types of causes come to mind when one tries to explain this disturbance: inappropriate emotional development, and constitutional and sociocultural factors.

INAPPROPRIATE EMOTIONAL DEVELOPMENT

The clinical history of borderline clients frequently shows that they come from highly disturbed families, with a high percentage of fights and separations. In general they were children who suffered a wide variety of childhood abuse, such as:

- Physical abuse — they were victims of physical violence or were present when family members were beaten.

- Sexual abuse — they experienced incestuous relationships and/or different forms of sexual insinuations on the part of adults near to them. Kroll, (1993:55-56) says: “Our unified point of view is that episodes of childhood sexual abuse have been the most frequent cause of problems that lead to the borderline personality.”

- Emotional abuse — they suffered neglect and lack of care on the parents’ part, where an inversion of dependence was frequent and the child began to take care of the parents rather than the opposite.

Self-destructive behavior in borderline clients would be unconscious ways of perpetuating abusive parents.

As far as development phases or at what moment in the client’s life this pathology takes root, the age of 18 to 30 months, shortly after learning how to walk is often mentioned in specialized literature (Mahler,1977:82-95; Erikson,1968:107-115). Parents in this period oscillate between controlling the child so that he does not hurt himself (since he recently began to walk), or becoming slightly absent – prematurely freed from caring for a child who now would rather explore the world than passively remain in the parents’ lap.

In reality, many parents cannot stand the children’s autonomy, become resentful and threaten them with abandonment. Malher describes this period as one of separation-individualization and believes that it is crucial to the development of a separate and secure self. He observes the children of mothers who either excessively abandon or overly possess them. These children develop an intense fear of abandonment or a premature omnipotence of the type “I don’t need anybody”, for fear of being suffocated.

Erikson describes this same phase, however, in terms of polarization between search for autonomy (attempt to impose their desires), and shame and doubt (in the face of failures). The child is still very dependent on the environment and his desire for self-affirmation, intense and violent, is greater than his ability of being able to impose himself. The borderline disturbance would be the consequence of an overly authoritarian upbringing, whose strict parents would always impose their desires on the child. With time, the attempts at self-affirmation succumb to the parents’ desires and the child ends up becoming used to always submitting himself, developing a feeling of doubt about his own capabilities and shame over his failures. Little by little, he stops trying to express his wishes.

CONSTITUTIONAL FACTORS

What is found in literature only suggests the presence of constitutional or hereditary factors in this condition’s etiology. For example, we know that siblings raised in the same family react to conflicts in different ways and only a few become borderline. This shows that something specific is needed to create one type of disease and not another. However, the individual who will later develop a borderline disturbance condition is, from childhood, a hypersensitive child who asks too much from his environment; he is more vulnerable, his needs are already shown to be very intense, his threshold for frustration is less, and his reactions more exaggerated.

It is also known that anti-depressant drugs and even anti-convulsive ones have the effect of alleviating symptoms in some borderline clients, in spite of not producing changes in basic personality.

Some other studies (Stewart and Montgomery, 1987:260-266) suggest a relationship between impulsive actions and abnormalities in the serotonin metabolism. Paul Andrulois and contributors (1980:47-66) point out the prevalence of neurological disorders such as hyperactivity, attention deficit disorders, epilepsy, etc. in borderline adolescents.

Finally, the presence of borderline parents (one or both) is extremely relevant in clinical histories. However, it is impossible to determine at this moment if this signifies a biological or psychological inheritance.

SOCIOCULTURAL FACTORS

Some authors correctly point out that there are sociocultural conditions contributing to the high incidence of narcissistic and borderline disturbances nowadays. The lack of a nuclear family structure composed of a mother and father who spend part of the day taking care of their children is one of the points most often cited in this type of analysis.

The change in the role of women over the last thirty years ended up radically changing the domestic routine: the famous “dad works and mom takes care of the kids” does not exist anymore, because now ”mom is also working outside of the home”. The children go to school early or remain in the care of others and old people are treated with disdain, which contributes to one losing the sense of pertinence and history, family closeness, and reference to consistent social roles.

Other factors like technological advances, especially in the computer area, contribute to people being more and more self-sufficient and having isolated work and study routines.

We live in a “borderland” where we stimulate assertiveness (which in extreme doses borders on aggressiveness), individualism (which favors loneliness and alienation) and self-preservation (“each one for himself, God for all”).

Our society needs consistency and reliability and is extremely alienating, favoring the appearance of a gamut of pathological behaviors, such as drug addiction, eating disorders, criminal behavior, etc.

Religious sects which try to organize reality in a very simple and polarized way – ”what is right and what is wrong” – gain popularity, perhaps as a reaction to a certain nostalgia for the old days when an organized family set up rules for how to live.

Kreisman (1991) makes an interesting comparison:

We quickly moved ourselves out of the explosive ‘We Decade’ of the 60’s into the narcissistic ‘I Decade’ of the 70’s, and from there to the materialistic and fast ‘Power Decade’ of the 80’s. Following these external changes, internal changes occurred in our values: from the ideology aimed towards others, the ‘peace, love, and brotherhood’ of the 60’s, to the ‘self-awareness’ of the 70’s, and from there to the ‘self-searching materialist’ of the 80’s.”

We know that many physical diseases like stress and all the disorders it produces, such as heart attacks, hypertension, etc., are closely related to lifestyle. Why not think the same about mental diseases? They are perhaps the psychological price we pay for our modernity.

PSYCHODYNAMIC – HOW BORDERLINE WORKS

Imagine a person who because of some congenital mistake is born without skin: any touch, even the lightest one would cause intense pain and reaction. This is the borderline; what he is missing is the “emotional skin”. Searching in a simplistic way for this pathology’s formula, we might think that an overly sensitive child in contact with an invalidating and multi-abusive environment, which destroys his basic self-confidence, has a tendency to develop defensive behaviors which are going to make up the very characteristics of this disturbance.

An environment that offers little validation is one, which does not teach the child how to adequately deal with his emotions. This learning process includes not only recognizing and naming the different emotions but also learning how to externalize them, hold them in, deal with frustrations, and above all to believe in one’s own emotional responses as a valid form of interpreting the facts (basic self-confidence). What is peculiar about this learning process is that it is in large part non-verbal: children learn not only through what adults say, but especially through subtly observing how they truly are and act.

These clients’ dysfunctional families tend to deal inconsistently with emotional manifestations: sometimes they ignore; sometimes they minimize and do not confirm; and in some extreme situations, they support and shelter. It is from this inconsistent performance that some children learn to focus their energy in accomplishing something “great”. This makes them feel noticed and valued, but detours the attention needed to adequately deal with reality away from routine matters. Little by little, they become less competent, more dependent, and less responsible than the other kids.

Because of this, the borderline as adult tries to keep himself close to a caregiver at all costs. His attitude is passive towards what he must do, but he is extremely active in seeking out someone that will do it for him. This is accomplished in many ways: for example, remaining chronically sick psychologically (depression, anorexia nervosa, alcoholism), or physically (colds that do not go away, general hypochondriac complaints); presenting himself as a very naive person without any maliciousness to then set up a manipulative relationship; creating a great amount of trouble in these relationships and being the eternal victim – never receiving justice and always fighting for his rights, etc.

The people who live around the borderline, therapists and family members, have the sensation that they are going around “walking on eggs”. They often say he is never satisfied and the situations that he creates do not seem to have a way out. He has to have something to complain about, perhaps, to keep someone close to him trying to satisfy him.

Besides this, as he comes from an environment that neglects the growing child’s basic dependence needs (Cukier, 1995:65-69), the borderline remains fixated on searching for a good caregiver, the “perfect” one. He idealizes and disappoints himself easily, becoming furious when noticing other’s imperfections. He is like a child who imagines that his mother knows and can do everything, and he does not admit the opposite hypothesis.

When he grows up, the borderline ends up reproducing the invalidating characteristics from his environment: he invalidates his own emotional experiences and looks for other interpretations of reality. He is incapable of solving routine problems and has generalized difficulties about “how to live”. He sets unrealistic goals for himself, does not value small achievements, and hates himself for his failures. The “shame” reaction, characteristic of these individuals, is the natural product of an environment that shames those who show emotional vulnerability. Besides this, his suffering and emotional reactions are extreme: what would be just embarrassing becomes deeply humiliating; displeasure can become hate; a slight fault becomes shame; apprehension becomes panic or terror.

A “prisoner” of his own emotions, he needs only a small motive to provoke strong reaction such as fits of rage and violence, which confuse and frighten the people around him and himself. He creates great tragedies which he complains about with increasing rage, blaming others for the situation which he finds himself in; the greater the fit of rage, the more the borderline convinces himself and tries to convince others that they are the ones responsible for his feelings. Along with that, his emotional responses are long lasting and take a long time to return to a more appropriate emotional level. This contributes to his being highly sensitive to the next emotional stimulus.

Having his emotional development stopped in the first phases, the borderline is a child in an adult’s body. And like all children he is impulsive, does not know how to wait, cannot stand being frustrated, has difficulty in symbolizing abstract concepts (like time for example), and is always trying to get everything that he wants, at any cost. Because of difficulty in making decisions and taking on responsibility, he tends to be more successful professionally in lesser positions, preferring well structured jobs that do not demand these abilities.

In short, the borderline has tremendous difficulty dealing appropriately with his emotions, and the therapist needs to find ways: first, not to allow himself to be destroyed by emotional macro-demonstrations; second, not to destroy the precarious emotional structure that these clients show (we must remember that they do not have “emotional skin”); and finally, he needs to find creative ways of performing small “skin grafts” and give these clients some covering so they can grow and develop with dignity.

BORDERLINE CLIENT PSYCHOTHERAPY

There are two fundamental difficulties in the therapeutic treatment of borderline clients:

The first is what we could call collision of objectives, which means those goals usually accepted as valid in therapy (understanding one’s own problems, “healing oneself”, undertaking constructive changes in one’s life, etc.) are not the client’s priority aims. Initially the client does not want to heal himself; to one extent, he is proud of the symptomatology he presents, as it is witness to the atrocities that he has gone through in life. What he is looking for in the therapeutic bond is exactly this witness function: someone who sees and disagrees with the injustices that were committed against him. And he also wants (it is there where the therapeutic job becomes much more complicated) the therapist to compensate him for everything that he has gone through; he wants to be gratified for his immediate needs, be taken care of and comforted. And even more, he wants an intense and special relationship to feel important. Apparently, these client’s implicit speech is always: “I cannot get better unless you, the therapist, demonstrate that you care about me personally.”

M., 16 years old; thinking about studying psychology and not being happy with her own appearance were what brought her to therapy. In the initial interview, her parents complained about her attempts to manipulate everyone in the family to get what she wanted.

From the start, she showed herself to be an extremely insecure person, anxious to please and full of anguish. She right away established an idealized bond with the therapist, not missing any opportunity to praise her (the therapist) or recommend her best friends for treatment with her.

To investigate the purpose of these recommendations and the exaggerated idealization, an internal psychodrama was proposed (since the client refused to dramatize). After the initial warm-up T (the therapist) suggested focusing on the therapeutic relationship using role reversals, so that she could experience the two sides of the bonds.

In her own role, M stated that she was fascinated by T and wanted to get her affection in a “special way”, because this therapist, unlike the previous one, seemed to be competent and capable of understanding her. In T’s role the client was unreachable, a person who did not need anything and was very appreciative of the client and her “presents” (recommendations), however, not to the point of allowing her into the so called “special place”.

Still in the internal psychodrama, using directions so that the client could distance herself from this relationship and observe it, T asked what other relationship in her life she had felt the same way, liking somebody so much that they seemed unattainable and that no matter how much she tried to please, she could not obtain what she most wanted.

The client then remembered a scene from her childhood when she was around 4 or 5 years old in which, being out with her real father, she did everything to seem unpleasant and deny his importance: she wanted to make it clear that she loved her stepfather more, recently married to her mother and who had assumed the position of full time father. M felt very grateful to her stepfather and could not stand the idea of displeasing him. Praising him in front of her real father constituted a way of paying him homage and simultaneously getting revenge for her father’s abandoning her.

Reviewing this scene led the client to notice several of her attempts throughout her life of feeling “special”; attempts which failed systematically without exception: she had not been special to her father, who rarely visited her; she was not special to her mother, who had many priorities; and she did not even remain special to her stepfather after the birth of the couple’s new children. Her performance in therapy was just one more attempt to reach this “special” place, unattainable.

The second great difficulty treating such clients in therapy is the relationship style that they try to establish with the therapist: at the same time that they try to gratify their needs, they do not believe that this can occur. Knowing that many of these people suffer distinct forms of child abuse from their caregivers, it is easy to imagine how any bond that implies personal care will soon be filled with distrust from the past. However, firmly establishing the therapeutic bond and the sensation of being understood and accepted is the first step for the borderline client to be able to throw himself into the painful attempt of looking at his difficulties and trying to change his life.

This sensation of being accepted and understood is unknown to the borderline, who will need to check it repeatedly. His movements will be ones of advance and retreat, and the therapist also needs to advance and retreat in order to maintain this balance: an exaggerated advance or a very great retreat on the therapist’s part could put the work already done in jeopardy. The client will be constantly testing how important he is to the therapist and at the slightest sign that could be interpreted as rejection, he can attack, sabotage, or interrupt the therapy.

I., 34 years old, with a history of many previous unsuccessful therapies, starts therapy deeply depressed, crying, and without hope. Since the beginning she has been very critical of everything that T says, the way she does it or the moment she does it; in short, she is always emphasizing disagreements and making T feel cornered, having to take a lot of care not to wound her.

No attempt at clearing up these misunderstandings was very successful because the client started a confrontation, opposing her version of the facts against T’s version. It always seemed that a judge would be necessary to decide what was right.

One day T, abstracting the client’s complaints from the verbal context, began to pay attention to how much she suffered from those episodes in which she was always crying a lot and seemed to feel anguished, and that she had been treated unjustly. She decided to apologize:

– I., somehow, some things I say or do unintentionally touch an old wound of yours. I want to apologize to you for this, because there is no way that I want to induce pain or harm on you. I believe that if we are patient together, we will discover where this very sensitive point is. For now, I would like you to accept my apology, even though I don’t know what I did to hurt you.

The client became completely bewildered by T’s attitude and crying, answered that T was not to blame and that she, the client, was always starting fights in all of her relationships and that a confrontational atmosphere was common in her life. T then asked her to create a character to represent this feeling of injustice that was always attacking her, and she produced a Medieval Crusader who defended the cause of the Holy Catholic Church. I. remained in therapy for four years in individual and group sessions; she never abandoned the Crusader as a reference for these confrontational states and could, through its inter-mediation, investigate several situations of domestic violence which she had suffered in childhood. She mentioned “that day when T apologized to her” several times throughout those four years, repeatedly assuring that that was the most important moment of the therapy, without which she could not have continued.

Besides these two fundamental difficulties there are many others throughout the therapeutic process: sometimes in the middle of some simple and unimportant speech, the client rapidly escalates to extremely controversial and confrontational themes. Others, on the contrary try to please the therapist, taking on his points of view and ways of thinking, and the therapist must be careful to prevent this from happening. Many borderline clients frankly try to seduce the therapist, probably showing the way they used to obtain consideration and perhaps even some kindness in the past. Many times the therapist is taken by surprise like in guerrilla warfare: very seductive forms of relationships alternating with very aggressive ones.

Lineham (1992) and Kroll (1994) call attention to the need for validation, support, and empathy for the borderline client exactly because he lived through childhood experiences that invalidated his right to exist, have personal limits, develop individuality, and confide in his own ability to perceive and judge reality.

To validate and affirm, give permission, and gratify are therapeutic actions that many times superimpose themselves, generating confusion crucial to the therapy going well. Validation and affirmation are actions which aim at helping the client to develop an intrinsic notion of personal value, through a therapeutic relationship of acceptance which tries to illuminate the client’s positive qualities, as few as they are. This is not always easy since clients bring a huge gamut of inadequate behaviors, and it is necessary to be careful not to artificially reinforce this, which in no way would contribute to therapy. The fact that the client has survived in extremely adverse circumstances and is seeking out therapy, already represents a praiseworthy action in itself, since it takes courage to confront this journey. Real affirmation and restraint also come out of the respect that the therapist has for the client, establishing limits that he, the therapist himself, respects such as: time, space, phone calls, etc.

P., 30 years old, gets home wanting attention from his wife, who at the same time is tired and busy with the couple’s two-year-old son. His wife’s attitude is immediately interpreted as rejection and P begins to attack her, first verbally and then physically. His discontentedness and frustration increase rapidly and he cannot contain himself.